The Book Contents

Dedication:

Table of Contents:

Forward 1 (Excerpts): Dr. Seyone, M.D., FRCPC:

Forward 2 (Excerpts): Jerome Morse, LL.B.:

Chapter 1 (Sample - Page 1 & 2):

CD-ROM:

| Click textbox below to Enlarge |

|

To see the Book's Table of Contents. Click here.

To be human is to be emotional. This is a truism of all human interaction. Even individuals who appear unemotional are emotional as apathy itself is an emotion.

There is no way that a human being, whether a lawyer, judge, juror or for that matter any kind of examiner of the human condition, can exist without emotional reactions. To do so, would not be human.

There is no way that a human being, whether a lawyer, judge, juror or for that matter any kind of examiner of the human condition, can exist without emotional reactions. To do so, would not be human.

Emotion in human interaction is often communicated by language. It is also communicated in subtle ways that are not obvious to the individuals having the interaction. This often leads us to form opinions about individuals quickly without necessarily having to go through a whole series of "explicit" questions to try and understand the other individual.

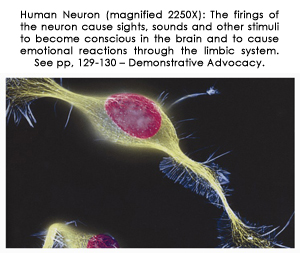

In fact, as described in early chapters of the book, all thought is a matter of impulses between neurons supported emotionally through the limbic system (see the image at the top left of a magnified human neuron, the firing of which is the root of all thought and language). Therefore emotion and reason work together and language, as expression of thought, is a product of the two.

This then can lead to bias. Bias can be partially understood as the emotional undertone of a relationship communicated imperfectly by language. Bias, especially in legal relationships, can lead to difficulties in the attempted impartial administration of the Rule of Law. This is especially so if the decision maker is biased in a particular direction. This book, with captivating imagery and style, traces the difficulties of the distinction back to the time of Aristotle who said that law is "reason unaffected by desire".

The Oxford English Dictionary, 10th Edition, defines an advocate as "a person who pleads a case on someone else's behalf".

No definition for advocacy is offered in the dictionary, but rather advocacy

is merely identified as a derivative of advocate. To this writer, whose context is almost 30 years as a trial lawyer in a civil

litigation practice in Ontario equally split between jury and non-jury trials, experience suggests a definition of advocacy to be

representation by persuasive communication to achieve the best possible result.

No definition for advocacy is offered in the dictionary, but rather advocacy

is merely identified as a derivative of advocate. To this writer, whose context is almost 30 years as a trial lawyer in a civil

litigation practice in Ontario equally split between jury and non-jury trials, experience suggests a definition of advocacy to be

representation by persuasive communication to achieve the best possible result.

The book Demonstrative Advocacy: Understanding and Constraining Partiality in Adjudication is a thoughtful and thought-provoking treatise that extensively and exhaustively examines the critical aspect of advocacy I characterize as persuasive communication.

I believe excellent teachers, entertainers and motivational speakers would agree that to achieve their objective to teach, entertain or motivate respectively, one must "know one's audience". The litigator's legal equivalent of knowing one's audience is to know and understand the bias (to be avoided/reduced when unfavourable and provoked/exploited when favourable) of the judge, jury and the opposing party and their counsel. In the latter case they are a highly relevant audience to be persuaded owing to how many civil litigation cases settle without trial (believed to be 95%).

There is however a very important distinction between teachers, entertainers, motivational speakers and litigators in that the "persuasion" in the case of all but the litigator conforms to or fits the bias of the audience, whereas advocates often have to overcome the bias of the adjudicator. This distinction is fully explored in Mr. Fancy's text.

I believe an important but overlooked attribute of excellent trial counsel is creativity. The creativity inherent in a fulsome utilization of demonstrative evidence by able counsel should not be underestimated. Mr. Fancy's text reveals a creative approach to be commended to advocates undertaking the challenge on how best to communicate persuasively.

For the past twenty centuries, faith was placed in judges to impartially examine the evidence and announce the decision. Originally, this faith was based upon divine intervention and then on a presumption of impartiality, guarded by an oath and procedural structures developed over time, to ensure judicial impartiality. However, the reality of adjudication raises serious questions about judicial impartiality, the ostensible fungibility of judges, and the effectiveness of those oaths and structures.

Read More.

For the past twenty centuries, faith was placed in judges to impartially examine the evidence and announce the decision. Originally, this faith was based upon divine intervention and then on a presumption of impartiality, guarded by an oath and procedural structures developed over time, to ensure judicial impartiality. However, the reality of adjudication raises serious questions about judicial impartiality, the ostensible fungibility of judges, and the effectiveness of those oaths and structures.

Read More.

To see sample images from various chapters Click here.